The Hooper Strait Lighthouse is the centerpiece of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in St. Michael's Maryland

The cupola now displays a lens of the

St. Michael's Bell Tower, located right next to the Lighthouse site. |

Come Explore the

History of the Chesapeake Bay at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum. That's what it

said on the sign, and that's what we were going to do. So we headed off to the beautiful little town of St. Michael's Maryland to see the museum and explore our first screw pile style lighthouse, the Hooper Strait Lighthouse. St. Michael's was once a very important center for shipbuilding and seafood harvesting. But today it is mainly known as a vacation stop with charming Inns, fine restaurants and unique antique shops. The museum is also a big pull for the town. A large working marina is part of the museum, so you'd be fine bringing your boat there. In Fact while we were in the museum gift shop, I met a guy that had recently been to Tybee Island, docking at the Marlin Marina. He was also traveling this time by boat and was docked at the museum marina. You can check on docking by calling 410-745-2916. The museum was really wonderful. We spent about 4 hours there looking at the displays of historic boats, a display on Steamboat building and how it impacted the Bay, and we got our hands in the water pulling up eel pots and learning just how brutally hard the profession of oystering was, and still is. But our main reason for being there, of course, was to see the Hooper Strait Lighthouse. Here is it's story. |

| A brief History of the

Hooper Strait Lighthouse

Built in 1879, the lighthouse that now graces the Chesapeake Bay's

Maritime Museum's Navy Point, once lit the way past Hooper Strait, some 39 miles south of

St. Michael's. Known as a screwpile, cottage-style lighthouse, Hooper Strait resembles a

small home that was built on special iron pilings that literally screwed into the Bay's

soft bottom. Because this style of lighthouse was actually located out in the

water, as opposed to on land, it was highly susceptible to damage from ice floes.

Consequently, the screwpiles, which burrowed down as deep as 10 feet, were an attempt to

stabilize the structures.

The Hooper Strait lighthouse was kept watch by two men whose duties included maintaining the building, standing watch all night to make sure the light remained lit, and ringing the fog bell during inclement weather. In some locations, families were permitted to live in the lighthouse, but Hooper Strait was not one of them. Consequently, there were no domestic niceties in the lighthouse. Water for drinking, bathing and cooking was collected from the roof's rain gutters in large 200 gallon cisterns, groceries were rationed and arrived once a week from the mainland, and the bathroom facilities were located outside on the deck. Originally, a platform attached to the pilings below the actual house served as the storage place for coal and wood for the stove as well as oil for the light. And the only means of entry into the lighthouse proper was a small sea hatch. The ground level staircase now attached to the structure was added for visitors' convenience, and was not a part of the original structure

All screwpile lighthouses on the Chesapeake Bay were built according

to a single plan but usage often varied. During its operation, the

four rooms on the first floor of the Hooper Strait lighthouse

included a kitchen, an office and two bedrooms. It was in these rooms that the

rainwater was collected in 200 gallon wooden tanks and purified

with chalk. The second floor, which is reached by a spiral staircase, has just two rooms: the watchroom and a spare bedroom for visiting Lighthouse Board inspectors. The watchroom contains the lighthouse's fog bell mechanism. Wound every two hours by hand, the enormous bell would toll out a signal unique to Hooper Strait. That way, mariners who were unable to see their exact location because of fog or bad weather, could determine their position by the lighthouse's bell sound. Once wound, the Hooper Strait bell would ring every 10 seconds. As the name implies, the most important aspect of the lighthouse was its light, which can be found on the third floor. Originally fitted with a fifth order Fresnel lens, the cupola now displays a lens of the fourth magnitude. Designed by French physicist Augustine Fresnel in 1822, the Fresnel Lens System consisted of six different sizes, the first being the largest and the sixth the smallest. Each lens is a series of prisms that bends and deflects light, carrying it a much further distance than ever possible before. Along the windows in the cupola hangs a piece of red glass. In a normal situation, mariners approaching Hooper Strait will see only white light. But as they near shoals areas, they begin to see red, meaning they need to turn back or risk running aground. Originally a fixed light signal, the Hooper Strait lighthouse now signals the letters CBMM for the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in Morse code. |

|

|

|

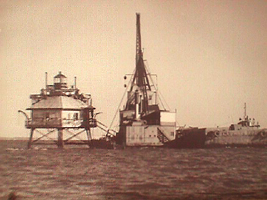

| Finding it more cost effective to automate the light rather than pay keepers to man it, the Hooper Strait Lighthouse was decommissioned in 1954 by the Coast Guard after 75 years of operation. Slated for demolition in 1966, the Museum purchased the building and moved it to its present site. Too large to be moved in one piece, it was cut in two just below the eaves and slowly transported on two separate barges up the Bay. The lighthouse was restored and opened to the Museum's public in 1967 where it remains one of the most popular exhibits. It is one of only three such lighthouses still in existence on the Chesapeake. | ||

The Museum is located at the end of Mill Street in St. Michael's Maryland. You can visit their Website at www.cbmm.org for more information. The hours of operation in the summer are 9am - 6pm daily.

Great Old Radio set on display in the Hooper Strait Lighthouse.

12/13/04 11:08:49 PM